The concept of health when it comes to technology usage is an ever-increasing one – and one where users, brands and vendors need to be equally mindful.

Much of the conversation tends to focus around social or smartphone ‘addiction’, and in particular its effect on younger minds. Yet research on the topic argues that things are a little more complicated. The most recent study, from the University of Oxford, polled 12,000 adolescents and concluded the effects of social media usage on teenage life satisfaction was limited, arguing family, friends, and school life all had a larger effect on wellbeing.

Whether it is through social or otherwise, the smartphone remains a near-impossible temptation to resist whatever one’s age. According to Deloitte’s most recent Global Mobile Consumer Survey, US consumers check their smartphones 52 times a day on average. 60% of those polled aged 18-34 admitted to smartphone overuse.

Scrolling has become second nature at this point, like breathing – and it has corrosive effects

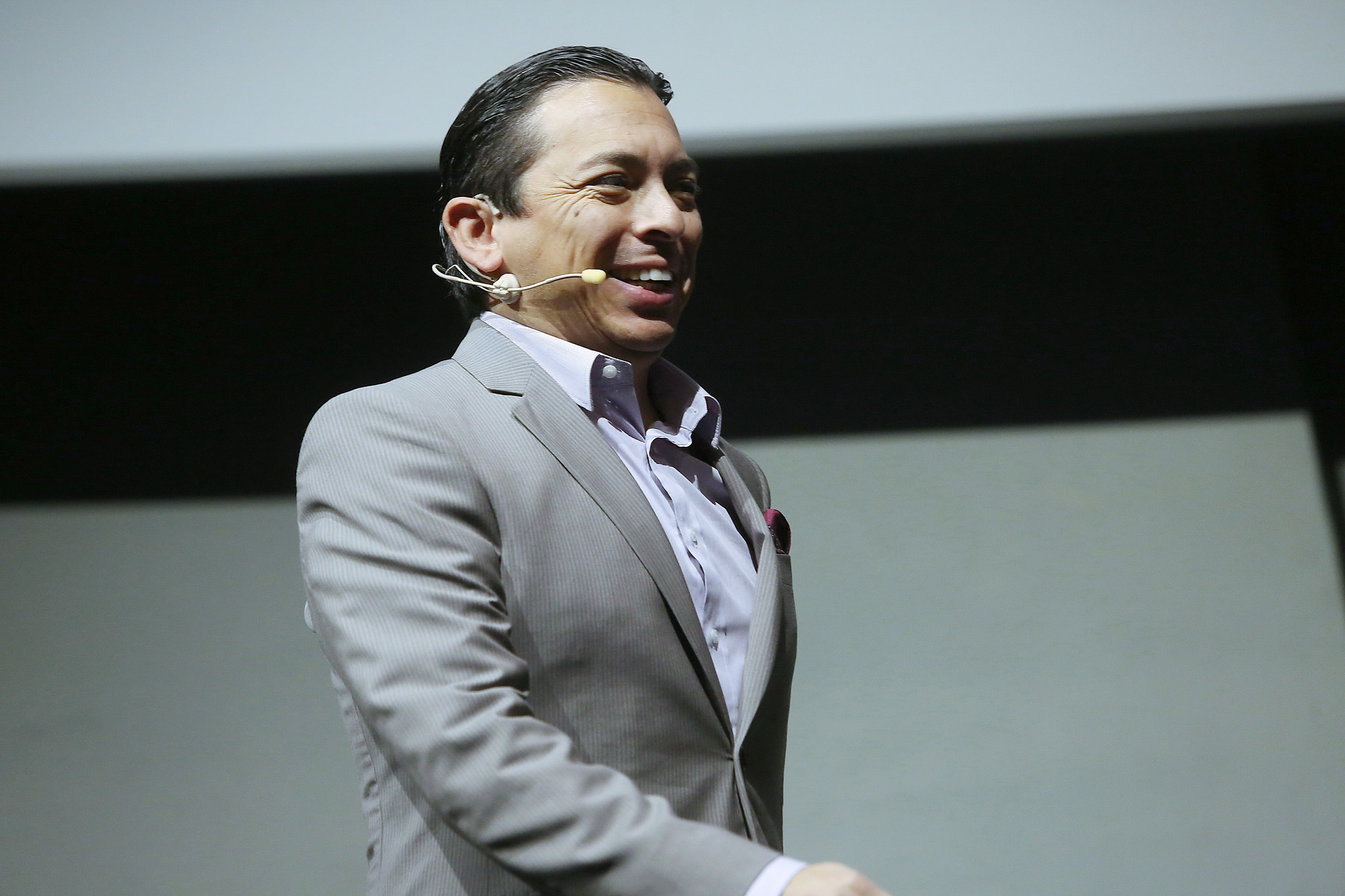

Brian Solis, principal analyst at Altimeter Group, puts it this way. Society today has become one where we consume more than we create. For content marketing teams stuck in the sausage machine, this statement can be seen as something of a vicious cycle. Do you stick to a rigid calendar? Do you take advantage of real-time marketing? Do you Frankenblog? 5,787 tweets are sent every second while approximately 80,000 hours of video is uploaded to YouTube every day. It is a chasm wherever you stand.

“This process of perpetual consumption has become second nature,” Solis tells MarketingTech. “Without even thinking, we’re scrolling with no greater purpose than just because it’s what our bodies and minds have come to expect. It’s second nature at this point, like breathing – and it has corrosive effects.”

Solis has a new book, Lifescale, which explores this distraction and how to overcome it. The theory presented is fivefold; firstly, to be present and mindful both in one’s physical and digital life; to ‘break the cycle of instant gratification’ and think critically and creatively; to live and work in the now without mentally wandering elsewhere; to waste less time on distractions; and to ‘foster creativity and imagination through powerful and life-changing daily rituals.’

The worst-case scenarios are frightening in their Machiavellianism. One example Solis cites is the Facetune selfie-taking app. It’s ‘fun, powerful and jam-packed with tons of retouching tools’, in the company’s own words. Any linguist would have a field day analysing such apps for their use of deliberatively positive language. Yet Solis had previously worked with a luxury brand and found the ‘unachievable’ expectations of beauty placed on girls and young women therein ‘astounding and very upsetting.’

Ultimately, the vast majority of the digital population has subconsciously picked up a series of bad habits. Like many entrenched habits, they can be difficult to overcome; but was the process of acquiring them so accidental? In The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, published earlier this year, author Shushana Zuboff disputes the narrative from the tech giants – Google in particular – that monetising a user’s ‘digital exhaust’ was not the original goal and just a piece of serendipity.

Not altogether surprisingly, Solis feels the same way. “The compulsion to endlessly scroll, to play games when we should be working, to check Facebook and email when it’s not necessary, are all the result of psychological manipulation by the industry that creates these platforms,” he says.

This manipulation, ‘persuasive design’, goes far beyond simple gamification. In 2015, Anders Toxboe, a UX designer who was then head of digital development at the Danish Broadcasting Corporation, published a series of cards aimed at helping UX professionals build persuasive design into their applications. Writing for UX Booth in 2018, he noted the ‘power and danger’ of this approach.

Toxboe’s best practices were aimed at helping users make decisions based on existing triggers based on desire – “you aren’t going to convince people they want something that they would otherwise not be interested in”, as he put it. Yet there came a caveat. “The danger of persuasive design lies in its power and the fact that it has taken powerful and complex psychological concepts and distilled them into easily digestible bits,” Toxboe warned. “User actions can’t be explained by a single root cause and behaviour doesn’t always happen in a direct cause-and-effect loop. We can lead users through tunnels, but we should always allow room for escape.”

“I’m definitely not against technology, but I am opposed to misinformation or suppressed information about the negative impact of technology,” argues Solis. “I want to know this information so I can make an informed decision about how I live my life and help others live their lives through my work. I want to be my most mindful, gracious, creative, and collaborative self.”

Hence Lifescale. The book is deliberately written to put the user on a path where several sideways steps are necessary; alongside chapter titles such as ‘energise’ and ‘realise’ are ones titled ‘reconsider’ and ‘reorient.’ It is evidently meant to signify the proverbial journey of a thousand steps – this is no quick fix.

“Turning off notifications and devices, deleting apps, digital detox, digital diets, productivity apps, meditation… they all help, but they’re treating the symptoms and not the core emotional, physical and psychological issues,” says Solis. “Like any addiction, the answers to adequately manage distractions and addiction are more than the superficial, trendy solutions touted by experts today.

“These wounds are deep and we’re treating them like minor cuts.”

One of the book’s other notable features is its colour off the page (above). While the vast majority of it is prose, there are pages for taking notes, cheat sheets, and vibrant yellow pull quotes. Its design was to emulate a digital experience on paper – an ‘analogue app’, as Solis puts it.

I’m definitely not against technology – but I am opposed to misinformation or suppressed information about the negative impact of technology

It is not exactly laid out as a hefty tome, nor is it meant to be – and the reason why makes perfect sense. If you are already struggling with the effects of digital addiction, are you going to leap at the chance of reading a more than 300-page book? Solis worries that those who most need this book may be too far gone – “focusing on validation, chasing popularity, worrying about being ‘on trend’ and living their ‘best’ (distracted) lives to realise they have a problem” – but for others willing to pull back, it is an easy, dippable feast.

“The book is written for distracted people who may not do a lot of reading,” says Solis. “It’s designed to visually stimulate your subconscious to keep reading and learning, building the discipline to do so along the way, while teaching readers via text and imagery.

“There’s a conscious system that allows us to focus on tasks at hand and then there is an unconscious network, that is very vulnerable to distraction,” Solis adds. “The book is designed to stoke positively. Lifescale is organised to help people ease through page by page, chapter by chapter, as they go on a journey to put their lives back in balance.”

Lifescale: How to Live a More Creative, Productive, and Happy Life (published by Wiley, April 2019) is available for purchase by visiting here.

Picture credit: 'CDO Summit Israel – Brian Solis', by Brian Solis, used under CC BY 2.0 / Modified from original

Interested in hearing leading global brands discuss subjects like this in person?

Interested in hearing leading global brands discuss subjects like this in person?

Find out more about Digital Marketing World Forum (#DMWF) Europe, London, North America, and Singapore.